Transcript

In psychology, the concept of “proximity” is a key variable in explaining behaviour in many circumstances. Proximity denotes both how physically close or emotionally close we are to something or someone. And differences in proximity can lead to varied outcomes.

One story that demonstrates the impact of proximity, is the classic trolley problem. You may recall a teacher explaining it to you when you were younger. If this doesn’t ring a bell, don’t worry, we’ll do a quick recap.

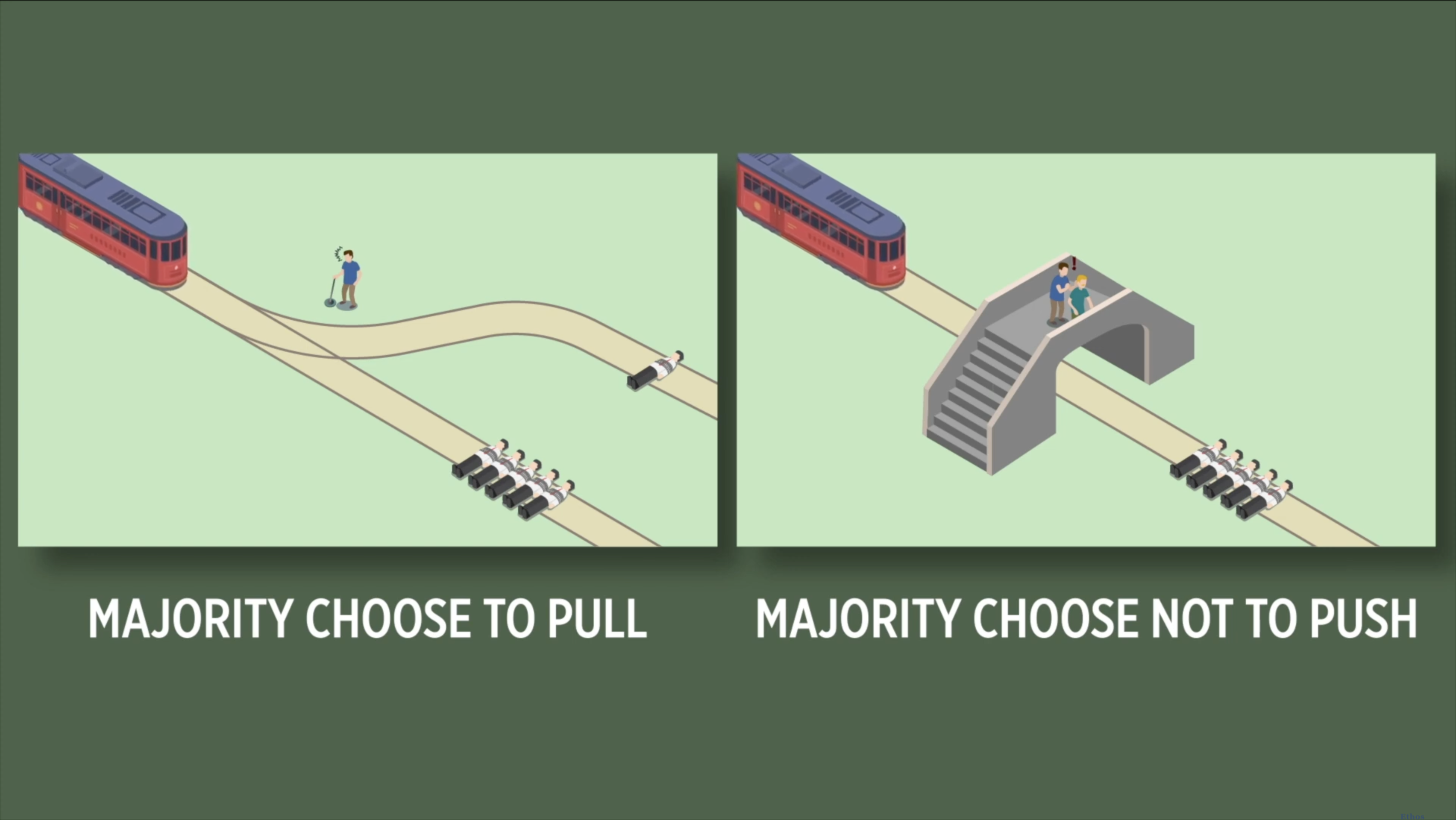

The typical version of the trolley problem usually compares two scenarios where there is a runaway trolley about to hit a group of five people.

In the first scenario, you have the choice to divert the trolley with a switch, which would change the trolley’s direction and kill one person instead of the group of five.

In the second scenario, instead of a switch, you are required to physically push a person in front of the trolley to stop it – thus saving the group of five – but killing the person you pushed.

Both actions lead to a similar outcome, and yet the way our brains process the situation is completely different.

The trolley problem has been reviewed and studied many times, and in each study, nearly everyone opts to divert the trolley using the switch, and nearly all object to pushing a person into its path. This dichotomy highlights the importance of proximity in people’s decision-making.

If an action is proximate, physically or emotionally, then we often rely on the “moral” centre of our brain to consider the dilemma. That is represented by the fact that almost everyone chooses to not push the man onto the tracks.

Conversely, if an action is non-proximate in nature, meaning the action and its outcome are separated even slightly, then we often rely on the “logic,” cost-benefit centre of our brain to consider the dilemma. That is represented by the fact that nearly everyone opts to pull the lever, even though the action leads to the same outcome as pushing the man.

Some examples of proximity came up from our students when we taught this class online. We’d be willing to donate our organs to save a loved one, but maybe not do the same thing for strangers. Or we often donate to our churches or charities in our local communities, but then don’t do the same thing for problems that are affecting people far away. Also, one student mentioned about stealing from a bank versus cybercrime. We are going to talk about issues of bank theft in the next couple of chapters, so remember that one for later.

The concept of proximity is very important because our world is increasingly distant and non-proximate in nature, resulting in our leaders increasingly using amoral, cost-benefit analysis when making decisions that can affect broad sectors of society.

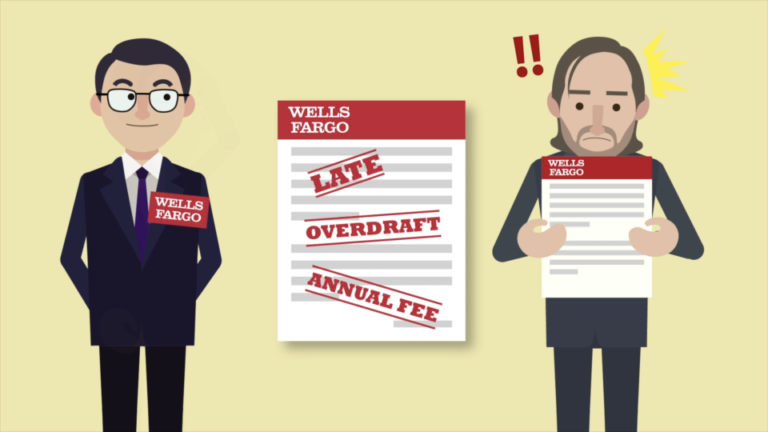

Let’s recall the Wells Fargo example we just discussed. If you compare Wells Fargo, a large, international bank, to perhaps a bank in a small town, the role of proximity is clear. Psychologically speaking, it’s generally much harder to cheat people we are proximate to, people we interact with on a daily basis, compared to a customer that is just a number, one person that is part of a mass.

Accordingly, the concept of proximity applies to FinTech too. One great outcome of FinTech is that it will provide financial access to a greater number of people, those who are unbanked or underbanked. At the same time, this technology will probably require less human interaction, meaning less proximity as well.

So does that mean as proximity declines, people may lean towards cheating each other more? Who knows, but what is clear is that we want new innovations to bring us closer together and not drive us further apart.

Discussion Questions

What happens when proximity declines?

Do you think, as proximity declines with technological innovations, that people will lean towards cheating each other more?

Additional Readings

- Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An fMRI Investigation of Emotional Engagement in Moral Judgment. Science, 293(5537), 2105-2108. Retrieved from https://science.sciencemag.org/content/293/5537/2105