Transcript

Banks have used the past decade since the financial crisis to rehabilitate their image, some more successful than others. But one bank has recently gone above and beyond in reigniting the general public’s disdain towards financial institutions. If banks are built on the foundation of consumer trust, Wells Fargo has systematically dismantled that trust leading to an uncertain future for that institution.

Wells Fargo has a really interesting history. It was established in 1852 in San Francisco during the gold rush, and as a result, has long been an integral part of the American financial landscape. When gold was discovered in California, Wells and Fargo – two entrepreneurs – decided to provide services relating to the transport and safekeeping of gold dust, gold coins, salaries, and other critical resources all across the US Western frontier.

You may have seen it before, but the stagecoach is actually the logo or symbol for Wells Fargo Bank. Before the advent of railroads, stagecoaches were considered the safest and most reliable form of transportation for people and valuables across the dangerous deserts of the Southwest United States. This was the age of the American cowboy, and those stagecoaches were the targets of some of the most notorious bandits of the time. You have probably seen movies with this type of scene – where a stagecoach driver and a guard sit on a seat. They usually carried sawed-off shotguns and revolvers and often had to fight their way past bandits in the rugged terrain.

Anyway, this is important because once again, the crux of the entire business model was based on trust. Trust that the Wells Fargo coach drivers wouldn’t steal the gold dust and bars they were carrying. Trust that the stage coaches and the roads built would provide reliable transit to ensure payment of railroad employees. Wells Fargo was so trusted by the railroad tycoons that it quickly established the largest fleet of stagecoaches in the world, helping to build one of the oldest and largest banks in the United States, eventually employing more than 200,000 people globally.

In September 2016, news emerged that employees at Wells Fargo, the world’s most valuable bank at the time, had created millions of fake bank and credit accounts that customers had never authorized.

Due to a high-pressure sales culture and an incentive-compensation program for employees to create new accounts, Wells Fargo employees had engaged in an array of immoral practices, such as fraudulently opening accounts, issuing ATM cards and assigning PIN numbers, faking signatures and using false email addresses. Customers had subsequently been hit with late fees, overdraft charges, annual fees, and other costs – all of which could affect their credit scores. When customers noticed the charges, employees would apologize and lie, saying oh, there just had been an administrative mistake.

This dishonest program was based on the internal goal of selling at least eight financial products to each customer, or what Wells Fargo called the “Gr-eight initiative.” These products included credit cards, savings accounts, investment accounts and more. Why eight you may ask? Because eight rhymed with great! No joke, that’s what they decided: the CEO said “Because eight rhymes with great,” therefore they arbitrarily decided that each customer should have 8 accounts with the bank.

Selling different accounts to bank clients is commonly known as cross-selling. Basically, if you go to a bank and open a savings account, they might ask you to open a checking account or buy an insurance plan. This is called cross-selling, and they wanted the average Wells Fargo customer to have 8 such accounts.

Why? Well, in part because it allowed the bank to make more money in fees. But to be honest, the fees were minimal and Wells Fargo didn’t really make much money off them. So then why would they do it? Why did the bank put so much pressure on their staff to cross-sell and push 8 accounts that managers across the bank started creating fake accounts?

The reason is that Wall Street analysts used data like “new accounts opened” as a key metric when evaluating a bank’s share price. That means, the more customer accounts Wells Fargo can show, the higher their stock price went, even if Wells Fargo wasn’t making any additional money.

And when analysts saw all the new customer accounts, the share price for Wells Fargo doubled between 2012 and 2015. And who makes money when the share price goes up? Well shareholders will, but in particular the executives and directors of the company who are compensated primarily in stock options.

So, in other words, even though Wells Fargo wasn’t making more money, or serving its customers better, the value of the shares doubled making a lot of money for the bank’s executives – the very people who created this horrible practice in the first place.

The high-pressure sales culture created by Wells Fargo bank executives, where you could face getting fired if not hit the cross-selling goals, created a toxic environment that pushed employees to fear for their jobs and make bad ethical choices, all while management turned a blind eye to the practice.

The program finally became public years after Wells Fargo’s management knew about the problem. When asked why he didn’t notify government officials as soon as he learned about the problem, then-CEO John Stumpf said, that the amount of money made by Wells Fargo from the program was immaterial to the bank’s size – and thus not important.

Of course, this incensed the public and lawmakers alike, and they demanded action. So what did Wells Fargo do? Well, they didn’t replace any of their senior management. Instead, they terminated nearly 5,300 mid-level employees, stating it was their fault for making up all the fake accounts. Not a single top-level executive was fired at that time.

Once again, this did not seem sufficient to the public and US lawmakers. US senators grilled Wells Fargo’s top management, and the media carried story after story detailing the bank’s actions – or perhaps more accurately, inaction.

After mounting pressure, then-CEO John Stumpf stepped down, as did Carrie Tolstedt, the head of the community banking division at Wells Fargo. But don’t feel too bad for either of them. When Ms. Tolstedt left Wells Fargo she received about 125 million USD equity compensation as a retirement package.

All in all, Wells Fargo had engineered what one analyst described as a “virtual fee-generating machine, through which its customers were harmed, its employees were blamed, and Wells Fargo [and it’s executives] reaped the profits.”

In light of the scandal, Wells Fargo and its new CEO, Tim Sloan – who was the bank’s former COO – emphasized that they would initiate refunds “as part of their ongoing efforts to rebuild trust.

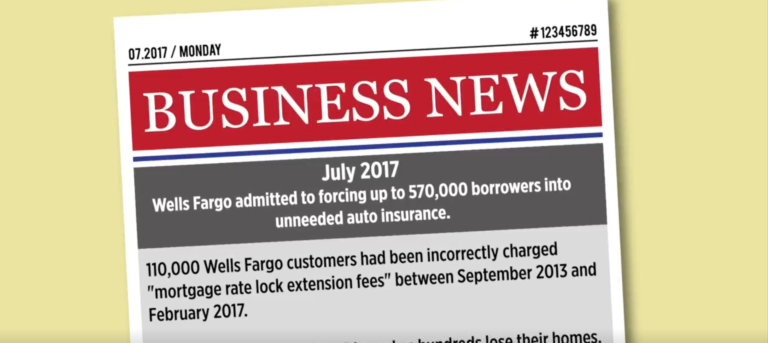

But Wells Fargo’s problems didn’t end there. Their unethical internal culture had permeated several of their businesses, leading to a string of scandals and investigations. For example: In July 2017, Wells Fargo admitted to forcing up to 570,000 borrowers into unneeded auto insurance. Reports also emerged that 110,000 customers had been incorrectly charged “mortgage rate lock extension fees” between September 2013 and February 2017. And last year news also emerged that a computer glitch at Wells Fargo caused hundreds of people to have their homes foreclosed on between 2010 and 2015.

As a consequence of these numerous scandals, the Federal Reserve announced on February 2, 2018 that Wells Fargo would not be allowed to grow its assets until it cleared up its act. An unprecedented punishment.

In May 2018, Wells Fargo launched a marketing campaign to emphasize the company’s commitment to re-establishing trust with its stakeholders. The commercial opens with the Old West origins of the bank, depicting its transition from horse riding, the iconic stagecoach, the steam boat, the train, its branches, its ATMs, now and its mobile systems – portraying its whole technological journey. The video then goes on to make references to the scandals, and illustrate how it is now a “new day at Wells Fargo.”

That new day and attempt to re-establishing trust, may have been another attempt in vain. Because, just a few months after, in August 2018, the Justice Department of the US government announced that Wells Fargo had agreed to pay a $2.1 billion fine for issuing mortgage loans it knew contained incorrect income information. The government said the loans contributed to the 2008 financial crisis that crippled the global economy.

If trust is a key component for the financial system and banks, what does the experience of Wells Fargo tell us about the financial system today? Do you feel like the Wells Fargo example is an outlier, and that most of the financial industry today can be trusted? Or, are you skeptical about the ethics of the broader industry as a whole?

Discussion Questions

- What is your opinion on the Wells Fargo case?

- Would you trust Wells Fargo as your bank after learning what they did? Why or why not?

Additional Readings

- Egan, M. (2017). Wells Fargo Dumps Toxic ‘Cross-Selling’ Metric. CNN. Retrieved from https://money.cnn.com/2017/01/13/investing/wells-fargo-cross-selling-fake-accounts/index.html

- Wells Fargo Just Got Hit With Another Penalty for the Financial Crisis. This Time, It’s $2.1 Billion. Fortune. Retrieved from http://fortune.com/2018/08/01/wells-fargo-financial-crisis-fine-mortgage-backed-security/

- Cavico, F., & Mujtaba, B. (2017). Wells Fargo’s Fake Accounts Scandal and its Legal and Ethical Implications for Management. S.A.M. Advanced Management Journal, 82(2), 4-19. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.eproxy.lib.hku.hk/docview/1926580720?accountid=14548 (paywall)

- Merle, R. (2017). Wells Fargo’s Scandal Damaged Their Credit Scores. What Does the Bank Owe Them? The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/in-wake-of-wells-fargo-scandal-whats-to-be-done-about-damaged-credit-scores/2017/08/18/f26d30e6-7c78-11e7-9d08-b79f191668ed_story.html (paywall)

- Verschoor, C. C. (2016). Lessons from the Wells Fargo Scandal. Strategic Finance. Retrieved from https://sfmagazine.com/post-entry/november-2016-lessons-from-the-wells-fargo-scandal/

- Volkov, M. (2018). Wells Fargo: Corporate Board Lessons Learned? Ethical Boardroom. Retrieved from https://ethicalboardroom.com/wells-fargo-corporate-board-lessons-learned/