Transcript

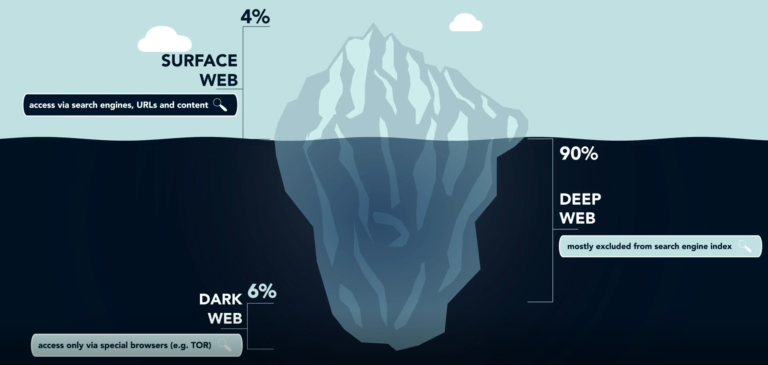

It was a great way for us to start thinking about the next topic. Fundamentally the core question is: do we have a fundamental right to privacy in our use of technologies? Or, by virtue of saying: I want to use this application, are we basically saying I am giving up some level of privacy? And is that why people are pushed into using things that are below the surface internet, be it the deep web or the dark web?

This is not a new question – it is a several centuries-old question that goes back to deeply held moral and legal beliefs in terms of the rights to privacy. A lot of major legal questions including abortion, and other things around the world actually get back to the same question of the right to privacy. What right do I have to engage in an activity within my own home as long as I’m not harming other people? And this is just an extension of that, where this data is being projected publicly and it’s a really complicated issue.

On the one hand, when we say the right, there has to be a granting of that right. There either needs to be a legal principle for example, within a constitution or within the law that says you have the right to this particular thing. In this case, the ownership or control of your own data.

Then you may even have a higher moral right, perhaps an Aristotle or even religious right to privacy. Say, I’m an individual and therefore I have the right to control who I am, my own image, my own likeness, the way I’m projected to society.

And beyond that, you then have those kinds of daily ticky-tacky opportunities that are contractual in nature where we often give away these rights. We agree to – not a violation of privacy – but certainly a limitation to our privacy and our own data.

One great example of this is when David Lee was teaching a class, he had a number of students read through the terms and conditions of a social media app that they had to click accept to use. Almost all of them are using the application, yet none of them have ever read the terms and conditions. As they went through it clause by clause, there were many things that surprised them, particularly about the use of their data.

We haven’t really gotten into AI and facial recognition software yet, but just imagine: we have potentially thousands and thousands of images of our faces that are out there. They are not supposed to be public, but we gave the rights to websites, apps and other software to publish them. And when you think about things like “deep fakes” – video technology that can now take images and alter them in a way that creates videos that are very realistic. Think about what would happen when these technologies are mature. We hope you start to question why you were so willing to put images of yourselves on the Internet.

There is another interesting side note. David Bishop has talked to a lot of parents in terms of the way they utilize or allow their children to utilize smartphones within their personal lives. This is something that we are all still wrestling with because we don’t understand the implications of this. So one thing that he and his wife decided to do is to never, or at least not for an extended period of time, put photos of their children online. And the primary reason goes back to this concept, this fundamental right to privacy.

Who has the right to decide to put your image publicly on the Internet?

Imagine if you’re going to your first job interview at 21 years old, and your potential employer has access to 10,000 images of you from the time that you were born to the time that you graduated – and you never consented to any of that. This is not prescribing a moral solution to other people, but this is an example of how we as a society now have to go back and redefine how we are willing and content to engage and utilize that technology.